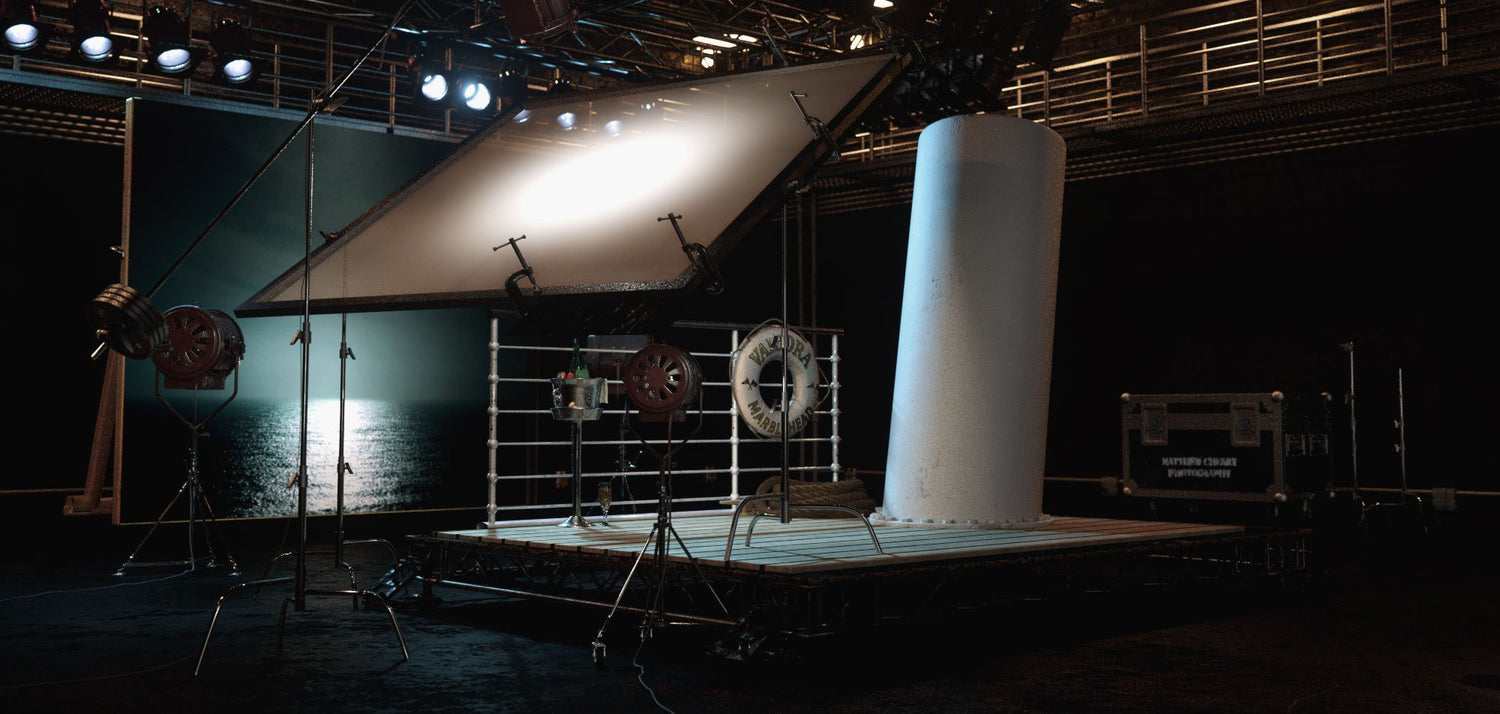

Photographers love to talk about cinematic imagery and ways to achieve it. Usually, when these discussions ensue, the focus tends to be on lighting or post-production techniques, such as cropping or color grading. Rarely, however, do we discuss the pre-production and production techniques used by filmmakers to create the worlds and characters that so captivate us on the big screen.

My goal, in this series of articles, is to open up the filmmaker’s toolbox and provide you with the means to better accomplish the goal of creating strong narrative work. Today we will take some time to discuss cinematic photography in terms of Art Direction, Production Design, and creating a set that is not only visually interesting but that serves as an expositional frame for your story.

The Importance of Story

If the story is the foundation of any narrative work, art direction is the scaffolding that allows that story to be built upon. So critical is art direction to the filmmaking process, an art director is often brought on board before a director has even been chosen. So, who is the Art Director, and why are they so important?

Unlike a novel, which might dedicate hundreds of pages to describing the world that its characters inhabit, a script, as it turns out, is an incredibly lean storytelling tool. A script’s only focus is the main elements of the story arc and the verbal interactions between characters that make that story arc possible – and even that is fungible in the service of the story.

While amateur scripts often discuss visuals, professional scripts rarely do. Instead, it is the Art Director’s job to create, and visually represent, the world in which the story unfolds. This is true whether we are talking about a blockbuster science-fiction franchise or a small indie film. It matters not if the story is told over a vast interstellar universe or in a single Manhattan apartment; the Art Director must carefully consider every element that exists in the frame.

Everything you see, no matter how small, is there for a reason, its purpose having been thought out by an art director; its form having been designed by a production designer and the physical object itself crafted by a myriad of production workers. Nothing you see in any frame of any film has been placed there by happenstance.

Don’t Say it, Show it

The Art Director’s attention to detail for sets, wardrobe, and props is integral to the storytelling process. Where a novel can take many pages to tell us what’s going on, that much expository dialog makes for a boring film.

The best filmmakers, instead, choose to show, rather than tell, that which can be presented visually. Sometimes this is very direct, meant to convey something very specific at a particular point in the story, other times it is to create a general mood for the viewer.

Imagine the following scene: Our intrepid hero is sitting on a sofa alone in a small apartment when the phone rings. He answers it and immediately we know it is his sister calling. He proceeds to spend the next minute of screen time rehashing how his wife left him, taking the kids with her. Then he spends another minute of precious screen time telling her how depressed he is because of it. Finally, he spends a third minute on the reason she called (the actual plot of the story).

Those first two minutes of conversation were completely unnecessary from the perspective of the character’s sister. He really wasn’t talking to her; he was talking to us, the viewers, bringing us up to speed on his character and his mental state. This is what’s known as exposition and, in this case, two minutes of screen time was devoted to it and it was delivered in the most boring way possible.

Let’s look at this scene again, but instead of our hero simply picking up the phone and talking, we see him rushing to open the door of his apartment to answer the ringing phone. As the camera follows him, we see his apartment is in disarray. It’s disheveled and obviously missing much of what was in it. By the décor of what’s left, it’s obvious that this isn’t some aging bachelor pad, this was the home of a family that is no more.

When the character picks up the phone and begins his dialog with his sister, he doesn’t bother telling us about the break-up, or that his wife took the kids, he gets right to the point while, at the same time, the camera shows us expositional elements that inform us, visually, of his recent past and his current mental state. In this way, the carefully crafted set serves as exposition.

Importance in Still Photography

The use of the set as exposition is even more important in narrative still photography. Whereas the filmmaker has time and dialog to work with, in addition to visuals; the still photographer only has a single image. Even when shooting a cohesive series, we are only presented with snippets, typically one shot per “scene,” of the overarching story.

Compressing our ability to tell stories down to a single frame requires a certain efficiency. So, how do we go about achieving it?

Step 1: Scripting and Character Development

Yes, even photoshoots should have a script. No, it doesn’t need to be formatted like a movie script, but it does need to effectively describe the story being told. This is useful not only for crystallizing your vision in your own mind but for communicating your vision to others.

Once you have a good description of what you are going to shoot, think about who you will be shooting. If you are shooting a portrait of an actual person, write down everything you know or can find out about that person and then distill this character description down to the essence that you are going to focus on.

If you are shooting an imagined character, either as a portfolio piece, fine art piece, or advertising piece, write out a character description complete with backstory. While this backstory may or may not be part of your interaction with the talent, it will certainly be important when thinking about your set.

Let’s revisit our previous example. What does our guy do for a living? What are his hobbies? Did his wife leave him because he was preoccupied with work? Was he having an affair? Was she?

If his character is a stereotypical stockbroker, alpha male type, who was having an affair with a younger woman when his slightly older trophy wife left him, the set we create would look far different than if he was an out of work factory worker whose wife left him because he wasn’t providing her the life she wanted.

Step 2: Creating your Mood Boards

Every Art Director begins their job researching their characters and the world they inhabit. Even when creating a fantasy universe, elements from other stories, art, film, history, and current events all play a role in creating their sets.

Again, using the above example, if our hero is an alpha male stockbroker, what does that mean? How does that person live? Sure, you can try to create it from whole-cloth, however, the results may be less than authentic. Even if you’re not going for pure authenticity, having elements that read correctly is important if you want the set you’re creating to have an expositional impact.

Take the time to research your characters using all the tools the internet so graciously provides us. Look up scenes from films that inspire you, look at furniture catalogs, anything that can inspire your vision. The reference images you collect are then turned into mood boards which will guide your set design.

While you may have one mood board for the overall shot, you may have an additional mood board for the set and yet another for the character (wardrobe, hair, makeup up, props).

Both characters may have the remnants of food that has been delivered, but the stockbroker probably has different culinary options available to him than the out of work factory worker. If our set is meant to show that the character has been drinking heavily for the past several days, one might be drinking a premium scotch while the other is drowning his sorrows in cheap beer.

Step 3: Design Without Limits

It is important at this stage to create an ideal version of your set. This is not the time to worry about how practical your set will be to create or how much actually building it will cost – there will be plenty of time for that later. Right now the goal is to design the perfect set on paper.

If your story takes place in a living room, start with the structure. What are the size and shape? Are the walls painted or wallpapered? Are there architectural details? Is the room filled with bright light through large windows, or is it dark and depressing with very little natural light? Is the floor hardwood with area rugs or carpeted? Again, use your reference photos as a guide.

From there move on to the next largest elements such as furniture, cabinets, etc. Where does your character shop? Where did his wife shop? Was he the designer in the family or was his wife?

Most importantly, for the scene we’ve been describing, what is missing? Perhaps the wife took her favorite sofa, the outline of which can be seen against the sun faded carpet that surrounds it — replaced, for now, by a lawn chair.

Once the large elements have been chosen, move on to the smaller items that add detail to a character’s environment — an overflowing ashtray, clothes that may be strewn about, dishware, bottles, family photos, books, etc. Consider each element and if it doesn’t contribute to the narrative, replace it, or remove it from your design entirely.

Step 4: The Art of Negotiation and Production Design

Up until now, you’ve worn two hats, that of Screenwriter and Art Director. Now it is time to pick up a third, the Producer’s hat. While it is the job of the Art Director to create the perfect world, it is the job of the Producer to say “No, we can’t afford that.” This is when the true creativity of the art department begins!

After all, the objection isn’t to the design, it’s to the cost, so how do we create something that looks just as good on film as it does in real life at a fraction of the cost?

Now is the time to pick up your fourth hat, that of the Production Designer.

It is the job of the Production Designer to make manifest the vision created by the art director. This might mean sourcing an object cheaply via craigslist and spending a bit of time to make it “screen ready,” or it might mean finding a way to borrow one or rent it cheaply.

If it’s an item that exists only in the art directors imagination, then it might mean finding bits and pieces at a hardware store or junkyard that, with a little elbow grease and some spray paint, can be made into a reasonable facsimile of the object that will look great in the photograph.

If your living room absolutely must have a stone wall, a little research will show you how to make one for just a few dollars using foam insulation and paint. While creating real walls for a real house can be a bit costly, building reusable theater flats costs very little.

What if you’re not a maker by nature, you ask? No problem! No matter where you live, I guarantee you there is an amateur theater company and someone in that theater company does set design. Creating beautiful sets out of relatively little is exactly what these folks love to do!

Find such a person and get them on your team! If you’re not doing client work and are simply doing portfolio development or creating personal art, you might be surprised how many folks will be willing to help out for little more than good pizza and beer, especially if they get to add their creativity to the mix.

Step 5: And Then There Was Light

The point of this article is to demonstrate that a set is more than a place for characters to interact, it is, in a sense, a character unto itself. Too often I see photographers take photos of well-lit talent on sets that lack the same illuminative care.

Hopefully, you’ve constructed your set early enough that you have some time between building it and your shoot. This time should be spent test lighting it. Just like each prop that exists in the frame must tell a story, so should the lighting, but how?

Go back to the script you wrote and read it again. Now, imagine that you had to tell the exact same story, but without anyone in the frame - essentially making it a large still-life photograph.

Consider all the elements you placed in the frame: the old lawn chair over the outline of a pilfered sofa, the cans of beer in a pile over in the corner, the old pizza boxes littering the old footlocker being used as a coffee table, the photos still hanging on the walls, and the outlines of those that are no longer there. Each of these elements become minor players and how you light the set will determine their importance.

The lighting will determine how the viewer's eye will move through the photograph; it will tell them what to notice immediately and what to find over time. Only when the set photographs perfectly, narratively, without anyone in the frame, then you are ready to begin principal photography.

Step 6: Sometimes You Have to Make Hard Decisions

Congratulations, you’ve been working diligently for the past two weeks writing, researching, designing, negotiating, redesigning, and building, and now it’s all starting to come together.

You have a set. Maybe it’s in a studio, maybe it’s in your garage or maybe it’s in your own living room, the contents of which are now piled up in your bedroom. Either way, it doesn’t matter, you get to experience the joy of walking around in a world of your own creation and that is no small thing.

You’re going to be proud of it. In fact, so much effort went into creating every single element of it, you’re now married to the sheer perfection of it.

That’s when it’s time to put on your Director’s hat and mess it all up.

Ok, maybe not all, but remember, everything in the frame MUST work to further the narrative visually. While we think we know how all of this will work during pre-production, it isn’t until you begin to test the set photographically that you will really know if all the elements work. Sometimes they do.

Other times, you’ll find that something you spent good money on or sweated over for a week, something you’re truly proud of and that you REALLY want in the shot, just doesn’t work. When that happens... Well, when that happens you have to lose it. Like a fallen soldier, you can lament the loss for a moment but then you need to move on.

The same is true for your carefully constructed lighting plan. What looked absolutely perfect without anyone in the frame may now feel too busy once you’ve lit your talent. Shadows cast where shadows must not be.

Even if you used stand-ins when test lighting your set to make sure all the lights worked as a cohesive lighting plan that aided the story, once you get your actual talent on set and begin working with them, the lighting will likely change or at the very least, need to be more controlled.

At the end of the day, the only thing that matters is the end result. Don’t let ego get in the way of a perfect shot.

Step 7: Pop Open the Champagne!

So much hard work was done, you have to celebrate! Maybe you did all of it yourself, but, if you’re really working to create the most cinematic images possible, you probably didn’t. You probably worked with a team of people from your wardrobe person, to your hair and makeup people, to your buddy with the cool tools that helped you build the set to your talent.

Everyone worked hard and everyone needs to know just how much their hard work is appreciated.

Myself, I always finish a shoot with a bottle of bubbly. No, it isn’t always the good stuff, but no one cares, just like the viewers of your photograph won’t care that the volcano in your shot is made of chicken wire and Plaster of Paris.

At the end of the day, the only thing that matters is that you came together to engage in the one activity, above all others, that makes us uniquely human — you told a story.

90 DAYS OF CONTENT

Over the next 90 days we are going to be working with some top artists to explore recommendations giving you solutions to problems we have all gone through. We are paying the writers a really fair wage for every original article, and we are writing about things that aren’t sponsored by any brand. There is no one but our opinion behind it. We would love it if you do use our affiliate links here so we can continue to keep writing awesome articles that you can trust.